Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2009 | Volume 58, Issue 6

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2009 | Volume 58, Issue 6

At dusk in early April 1866, a large crowd filed into Representatives Hall of the imposing Illinois Capitol in Springfield. Just 11 months earlier, President Lincoln’s rapidly blackening body had lain here in state as thousands of townspeople had filed past to say goodbye.

Now many of the same people gathered to hear a lecture entitled “The Assassination and Its Consequences,” delivered by the country’s foremost abolitionist, Frederick Douglass. For several months, the powerful black orator had given the same speech across the nation, but this venue, more than any other, lent extraordinary gravity to his words. In the great room Lincoln had accepted the 1858 Republican Senate nomination and delivered his controversial “House Divided” speech. Though the obscure Illinois lawyer would lose that contest to his longtime rival Stephen A. Douglas, he found himself unexpectedly propelled to the presidency. Lincoln had also argued in front of the Illinois Supreme Court more than 200 times in this building.

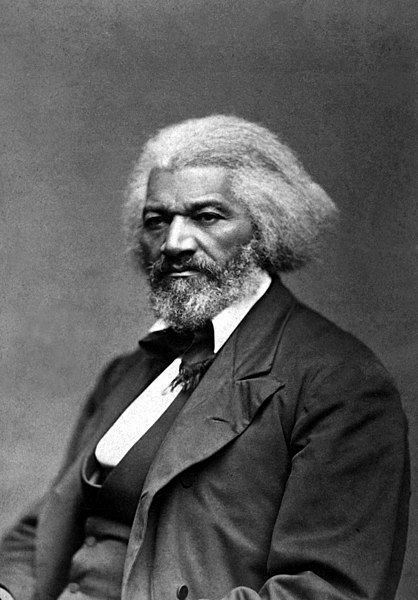

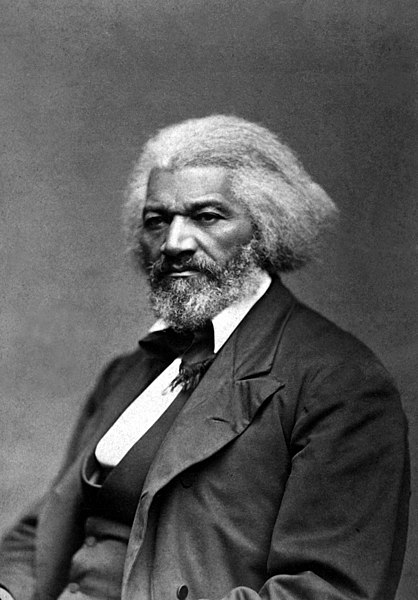

Standing on the podium, Douglass immediately commanded attention with his splendid mane of graying hair swept back from his broad forehead, his blazing brown eyes, deep regal voice, and overwhelming physical presence. “Prior to the Civil War,” he began, “there was apparently no danger menacing our country, but a few farseeing men foresaw the calamities that have come upon us, and their warnings were treated as idle talk . . . The few listen and the many pass on, unheeding the precipice over which they are being hurled."

The slave child Frederick Bailey, born in 1818, had gradually transformed himself into the master orator Frederick Douglass, internationally known by the 1840s through the force of his eloquence fused to a compelling dignity. Only fellow abolitionist Wendell Phillips equaled him as a speaker. No one on the national stage could match the powerful, redemptive quality of his life story, which was compelling for more than his daring escape from slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. With dogged perseverance, he had toured for years from town to town, often at the risk of his life, to evoke the horrors of human bondage. He had written a best-selling personal testimony about his struggle for freedom, edited the nation’s most notable black newspaper, and finally, through his forceful recruitment of black soldiers, he had become the principal voice of his people.

The intent of Douglass’s talk in Springfield was not to dwell on that past, but to confront the new realities facing a victorious North and a nation without Lincoln. “The danger impending