Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2009 | Volume 58, Issue 6

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2009 | Volume 58, Issue 6

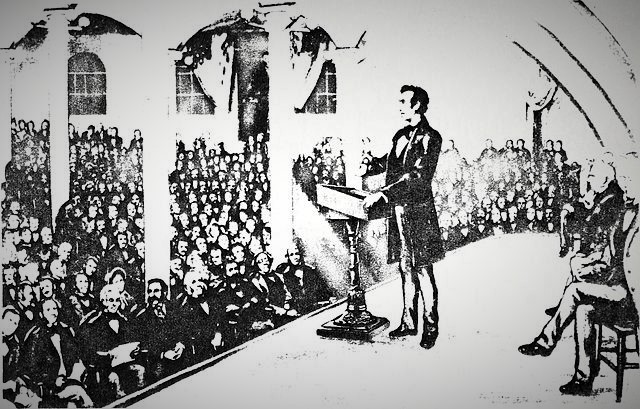

On February 27, 1860, Abraham Lincoln stood before a crowd of 1500 at Cooper Union Hall in New York City. Until he had declared his candidacy for president of the United States, the former one-term Congressman had drawn little attention outside his home state of Illinois. Now the rail-thin prairie lawyer attracted a sizeable audience, including the “pick and flower of New York culture,” along with an army of journalists eager to record and reprint his words.

“Let us have faith that right makes might,” Lincoln challenged his listeners, “and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.” Here was no stump speech, but rather a powerful argument that extending slavery to new territories was not only wrong but also counter to the intent of the founding fathers. His delivery was eloquent, the argument carefully reasoned and fact-filled.

Had Lincoln not delivered such a triumphant address before the sophisticated and demanding audience that night, it is possible that he would not have been nominated, much less elected, to the presidency the following November. And, had Lincoln not won the White House in 1860, the United States—or the countries it might have fractured into—would probably look very different today.

How Lincoln crafted this brilliant and critical delivery has remained the topic of some debate over the years in part prompted by an interaction he had the following month. Lincoln had traveled from Springfield to Chicago to appear in what turned out to be his last big trial: the famous "sandbar case," a complex civil dispute in which he represented his most important client, Illinois Central.

While in the city, Lincoln also agreed to sit for a wet-plaster life mask at the studio of sculptor Leonard Wells Volk. Chatting in the studio, their conversation turned to Lincoln’s nationally noticed appearance in New York a few weeks earlier. As Volk remembered it, Lincoln told him the astonishing fact “that he had arranged and composed this speech in his mind while going on the cars from Camden to Jersey City.”

By the time Volk published this revelation, almost as a postscript, in his engaging 1881 reminiscence of the sitting, Lincoln’s myth-worthy creative acumen and almost saintly self- effacement had emerged as crucial elements of the reigning image of the Great Emancipator. Volk’s recollection about the Cooper Union speech, clouded though it may have been by the passage of time, seemed well in keeping with the hagiography of the day. Besides, an orator who had supposedly been able to pronounce his masterful 1861 farewell to Springfield extemporaneously, or to create his greatest masterpiece on the back of an envelope while riding on a train to Gettysburg, surely could have written his Cooper Union address on a train in the few hours from Camden