Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2010, Summer 2025 | Volume 59, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2010, Summer 2025 | Volume 59, Issue 4

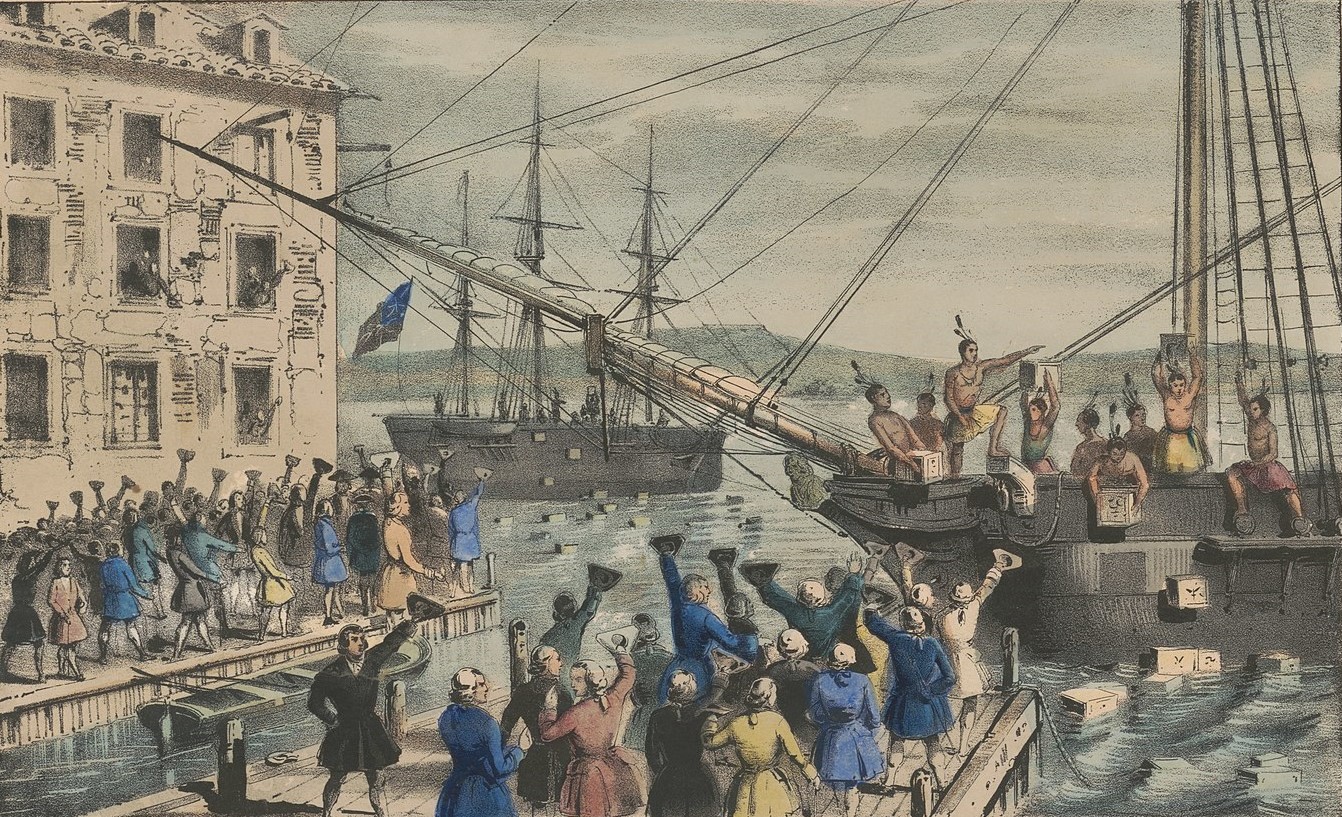

On the evening of December 16, 1773, in Boston, several score Americans, some badly disguised as Mohawk Indians, their faces smudged with blacksmith’s coal dust, ran down to Griffin’s Wharf, where they boarded three British vessels. Within three hours, the men—members of the Sons of Liberty, an intercolonial association bent on resisting British law—had cracked open more than 300 crates of English tea with hatchets and clubs, then poured the contents into Boston Harbor.

News of the “Boston Tea Party” quickly spread throughout the colonies, and other seaports soon staged their own tea parties. While tensions between the Americans and the British had simmered for the past several years, there had been few acts of outright rebellion. The tea party lit the smoldering coals of discontent and ignited events that would lead to rebellion, war, and, finally, independence.

The first bloodshed of the Revolution had occurred nearly three years earlier, on March 5, 1770. A continual source of tension was the taxes levied by the British government on the colonists. Although British Prime Minister Lord North tried to placate the colonists with a pledge of no new taxes from London, on March 5 a mob of radical Americans, unaware of the announcement, had attacked the customhouse in Boston, prompting a confrontation with British redcoats. The crowd had begun to throw hard-packed snowballs at the British sentries guarding the customhouse. Goaded beyond endurance, the soldiers began to fire, killing five people and wounding several others in what came to be known as the Boston Massacre.

But North’s concessions had dampened the rebellious attitude that had been spreading through the colonies, causing a backlash among moderates who believed that the Sons of Liberty presented a greater danger to America than did British taxes and troops. By October 1770, Boston’s merchants announced that they would no longer honor the patriots’ boycott of British imports, and it looked as though the flames of rebellion had been snuffed out. Although some of the more ardent revolutionaries kept in contact through committees of correspondence that issued statements of colonial rights and grievances—Samuel Adams pledging that “Where there is a Sparck of patriotic fire, we will enkindle it”—no more significant incidents of violence would occur until late 1773.

During this reprieve North became more concerned with Britain’s economic policies than with colonial discontent. The behemoth of British international trade, the East India Company, teetered on the verge of insolvency. Because many leading British politicians were company shareholders, saving it was of particular concern to Parliament. One potential solution seemed at hand: the company’s London warehouse held more than 17 million pounds of tea. If these stores could be