Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1955 | Volume 6, Issue 3

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1955 | Volume 6, Issue 3

Knox was one of those providential characters which spring up in emergencies, as if they were formed by and for the occasion.

—Washington Irving, Life of George Washington.

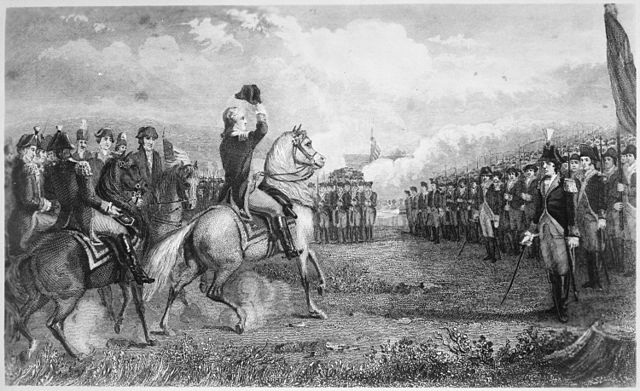

By the time Washington took command of the American Army at Cambridge in July, 1775, his troops had dug fortifications on the hilltops ringing Boston. The British, who had occupied the city for over a year, were pinned down but could not be starved out as long as their navy kept the port open. The Americans lacked siege guns and trained storm troops. On the other hand, General Gage, the British commander, had been made cautious by the mauling his infantry had received on the Concord expedition and at Bunker Hill.

American artillery could threaten British shipping only on one of the two heights situated at opposite tips of the crescent formed by the American lines: Bunker Hill, north of Boston, and Dorchester Heights, across the bay to the southeast. Bunker Hill had been won by the British and neither side was yet ready to fight for Dorchester Heights—the British because of Gage’s reluctance to risk the loss of more troops difficult to replace; the Americans because they lacked the artillery to take advantage of the superior location once it had been occupied.

The military situation had reached a frustrating stalemate. In keeping secret his shortage of arms and powder, Washington had divested himself of any ostensible reason, in the eyes of his men and the Continental Congress, for not taking Boston. His troops, after all, outnumbered the British better than two to one. The inactivity was fomenting low morale and wholesale desertions. In a few months, the year’s enlistment period would be up for Washington’s army and the straws in the wind were enough to inform him that there would be few soldiers who would remain for a second hitch. Supplied with artillery, he could quickly place the guns within effective range of the British land defenses and naval vessels and drive Gage out of Boston.

Where were enough artillery pieces to be obtained? Even if they could be spared from defense points elsewhere in the colonies, the logistical problem of transporting them in time and in sufficient number to be worthwhile could not be overcome.

Washington’s answer came from one of the few men he had come to like, trust and respect since the general’s arrival in Cambridge: Henry Knox, a civilian volunteer, a bookseller.

Knox was a native of Boston. His parents were Scotch-Irish who had emigrated from northern Ireland. The elder Knox was a ship’s master who died bankrupt in the West Indies when Henry was twelve. Henry was the seventh of ten sons and one of only four to survive childhood. Of