Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2010 | Volume 60, Issue 3

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2010 | Volume 60, Issue 3

On Sunday, May 14, 1865, Benjamin Brown French, commissioner of public buildings for the District of Columbia, left his home on Capitol Hill to buy a copy of the Daily Morning Chronicle. “When I came up from breakfast I went out and got the Chronicle,” he wrote in his journal, “and the first thing that met my eyes was ‘Capture of Jeff Davis’ in letters two inches long. Thank God we have got the arch traitor at last.”

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles also noted the Confederate president’s capture in his diary: “Intelligence was received this morning of the capture of Jefferson Davis in southern Georgia. I met Secretary of War Edwin Stanton this Sunday p.m. at Seward’s, who says Davis was taken disguised in women’s clothes. A tame and ignoble letting-down of the traitor.”

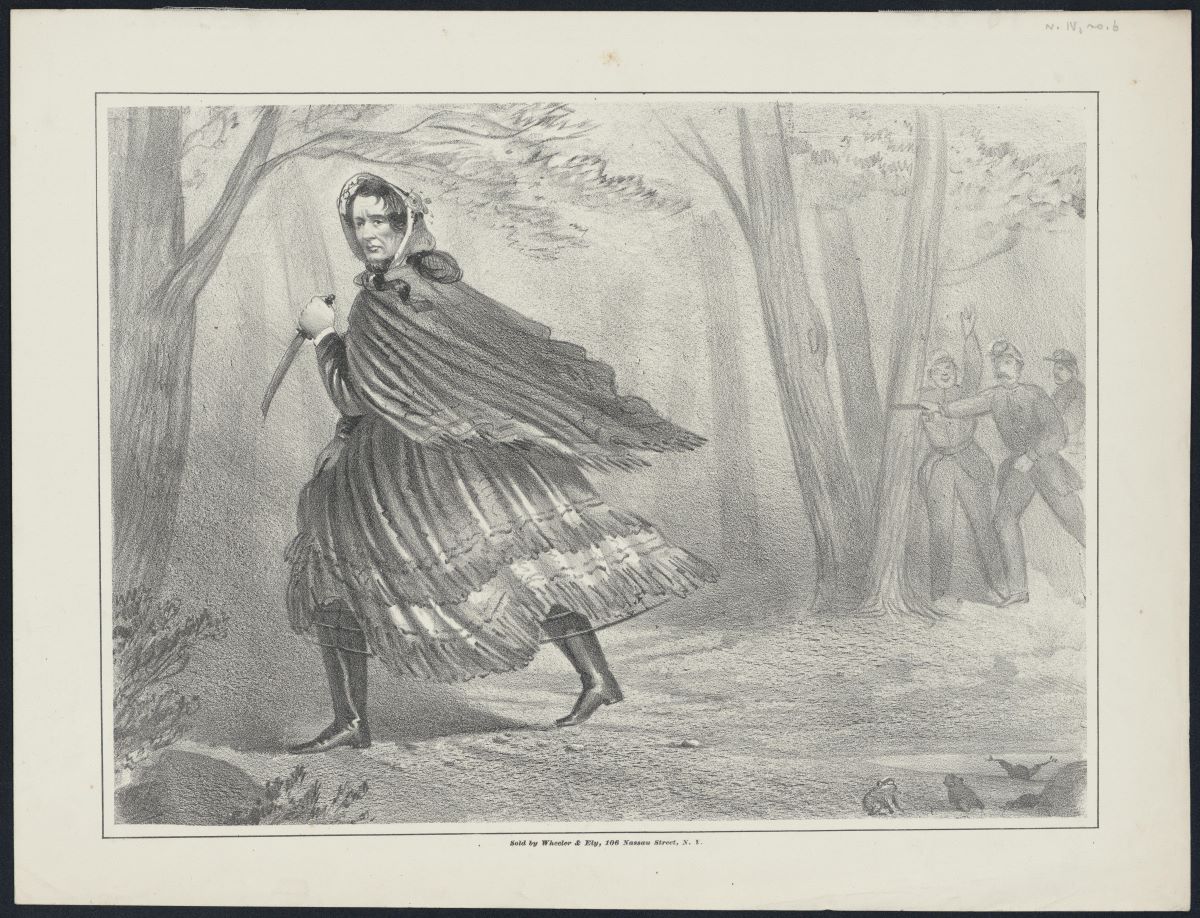

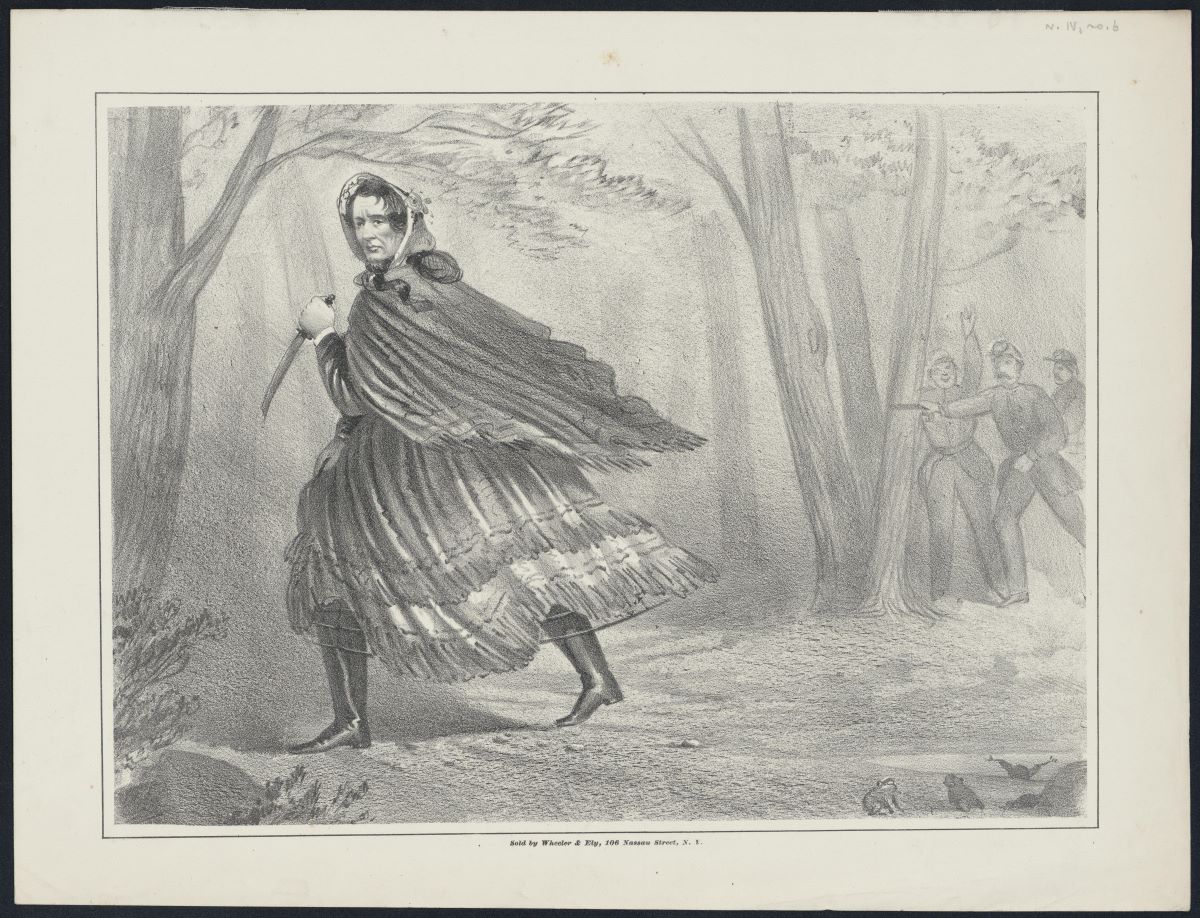

The story of Jefferson Davis’ capture in a dress took on a life of its own, as one Northern cartoonist after another used his imagination to depict the event. Printmakers published more than 20 different lithographs of merciless caricatures depicting Davis in a frilly bonnet and voluminous skirt, clutching a knife and bags of gold as he fled Union troopers. These cartoons were accompanied with mocking captions, many of them delighting in sexual puns and innuendoes, and many putting shameful words in Davis’s mouth. Over the generations, fact and myth have comingled concerning the details of Davis’s final capture. Had he borrowed his wife’s dress to evade the Union cavalry? How much of the unflattering post capture cartoons, news reports, and song lyrics sprang from the deep bitterness Northerners held for the man who symbolized the Confederacy?

A little more than a month earlier, on April 10, President Abraham Lincoln and the inhabitants of the nation’s capital woke to the sound of an artillery barrage at dawn. Journalist Noah Brooks ate breakfast with the president that morning and later recalled that “A great boom startled the misty air of Washington, shaking the very earth, and breaking windows of houses about Lafayette Square. . . . Boom! Boom! Went the guns, until five hundred were fired.”

Lincoln had received the word the night before that Lee and his army had surrendered to Grant. The early morning salute “was Secretary of War Stanton’s way of telling the people that the Army of North Virginia had at last laid down its arms, and that peace had come again,” Brooks wrote. “Guns are firing, bells ringing, flags flying, men laughing, children cheering; all, all are jubilant.”

The whereabouts of the Confederate president, who had fled the capital of Richmond eight days earlier, was unknown. “It is doubtful whether Jeff Davis will ever be captured,” noted the New York Times. “He is, probably, already in direct flight for Mexico.”

That day