Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2010 | Volume 59, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2010 | Volume 59, Issue 4

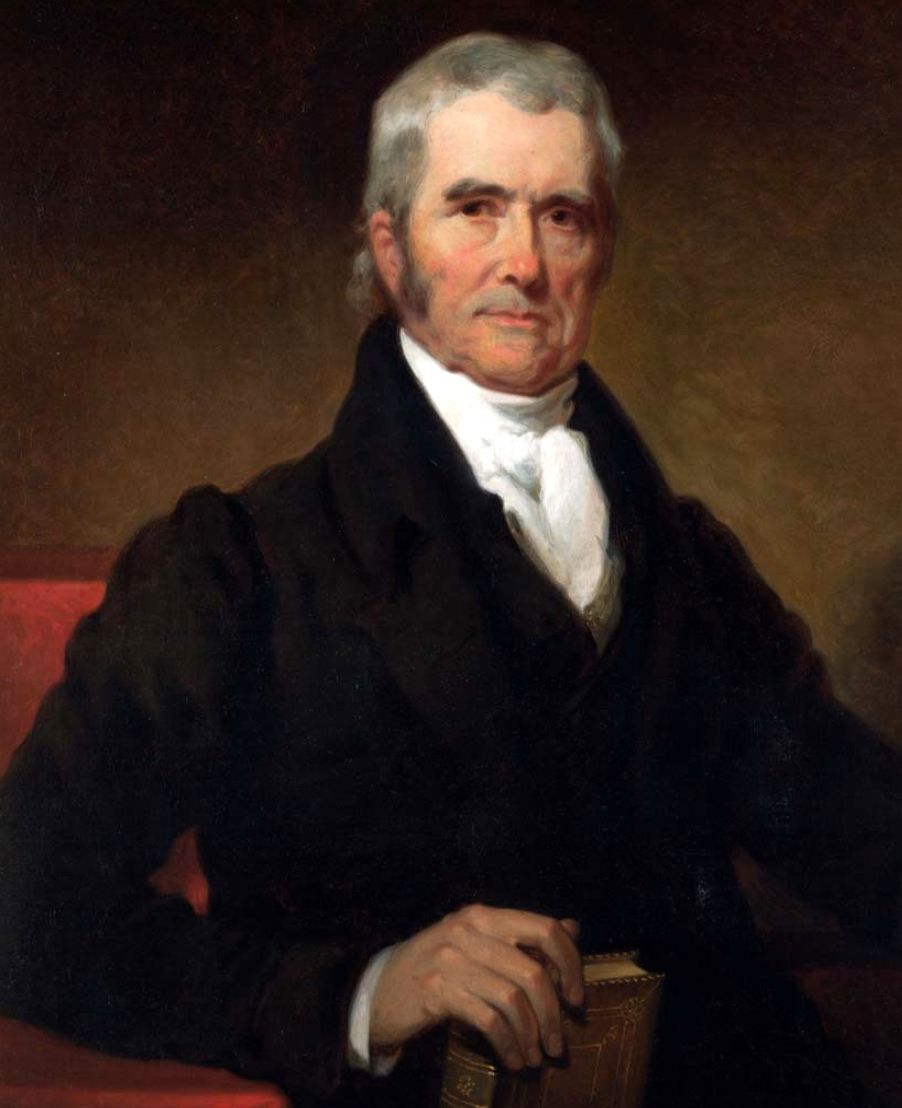

Most jurists and constitutional scholars today would probably contend that the most controlling precedent to be set in the early republic was laid down in the 1803 Marbury v. Madison decision. While a formidable ruling, it was not, however, the decisive moment—at least not to people at the time. The hinge event in the early history of the judiciary was President John Adams’s appointment of John Marshall as chief justice of the Supreme Court in 1801. More important than Marshall’s Marbury decision, which was incidental and scarcely as momentous in 1803 as it later came to be, was his campaign to save not just the Court’s role in interpreting the Constitution but its independent existence. Without Marshall’s shrewd maneuvering in the decade or so following his appointment, the Court would have turned out a substantially different and much weaker institution than it became.

When Marshall took office, the Federalist-dominated Supreme Court was a beleaguered institution, increasingly vulnerable to attacks by the Jeffersonian Republicans as aristocratic and out of touch with the popular majority. Consequently, it had become difficult to find able nominees for vacancies. Between 1789 and 1801, 12 men had sat on the bench, of whom five, including two chief justices, had resigned. The Court even had trouble mustering a quorum, forcing cases to be carried over and sometimes compelling sessions to be cancelled entirely. In 1801, President John Adams had initially wanted to reappoint John Jay, the first chief justice in 1789. But Jay declined, explaining that the Court had none of the necessary “Energy, weight and Dignity” to support the national government and little likelihood of acquiring any.

More alarming, the Jeffersonian Republicans who had just seized the White House and control of Congress were set on yet further reducing the power of the Federalist-dominated judiciary, the only branch of the federal government they did not control. The Congress attempted to use impeachment as a crude but effective method of clearing away obnoxious Federalist judges. Having put matters to the test by impeaching and removing an alcoholic and partisan New Hampshire federal district judge, it turned to Associate Justice Samuel Chase, the Court’s most overbearing Federalist. If Chase were convicted, many Republicans hoped to move next against the other justices, including Marshall. Although the Senate narrowly failed to convict Chase, the Republican threat to the judiciary remained.

These were the dangerous circumstances that Marshall had to deal with; and deal with them he did, superbly. In the end his greatest achievement was maintaining the Court in the amplitude of its authority and asserting its independence within so hostile a climate. He began by changing the Court’s lordly image. Using his extraordinary charm, he persuaded his fellow justices to shed their feudal scarlet and ermine robes in favor of a plain republican