Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2011 | Volume 61, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2011 | Volume 61, Issue 1

Nothing in his childhood in Gloucestershire’s quiet parish of Down Hatherley had prepared 43-year-old Button Gwinnett of Georgia for the fierce politics that he encountered after signing the Declaration of Independence on August 2, 1776. One rivalry would turn so bitter that it would cut short his promising career. Violence, sometimes lethal, was an integral part of the fabric of the early American political discourse.

Gwinnett’s problems began when the Continental Congress awarded a military commission he craved to his chief political rival, Lachlan McIntosh, “the handsomest man in Georgia.” The two men represented opposite sides in an intense power struggle. McIntosh belonged to the conservatives, who lived mostly in and around Savannah and had run things for a long time. Newcomers Gwinnett and his friends came from the back country and outlying coastal counties. Evidence of the Gwinnett group’s increasing political clout emerged when Georgia’s assembly tapped him to serve out Archibald Bulloch’s term after the governor died suddenly in 1777.

In pursuit of glory on the battlefield, Gwinnett organized an expedition against British-held St. Augustine and eastern Florida in a bid to secure Georgia’s southern border. General McIntosh forbade Continental Army troops from joining the venture, which ended in mortifying failure. McIntosh publicly blamed the fiasco on Gwinnett, which helped defeat his rival’s bid to win a full term as governor.

Gwinnett mustered enough friends in the legislature to win exoneration in an official inquiry. An angry McIntosh rose in the assembly and called his foe “a scoundrel and a lying rascal.” That characterization forced Gwinnett either to challenge McIntosh to a duel or to retire from public life as coward, no longer worthy to be considered a gentleman

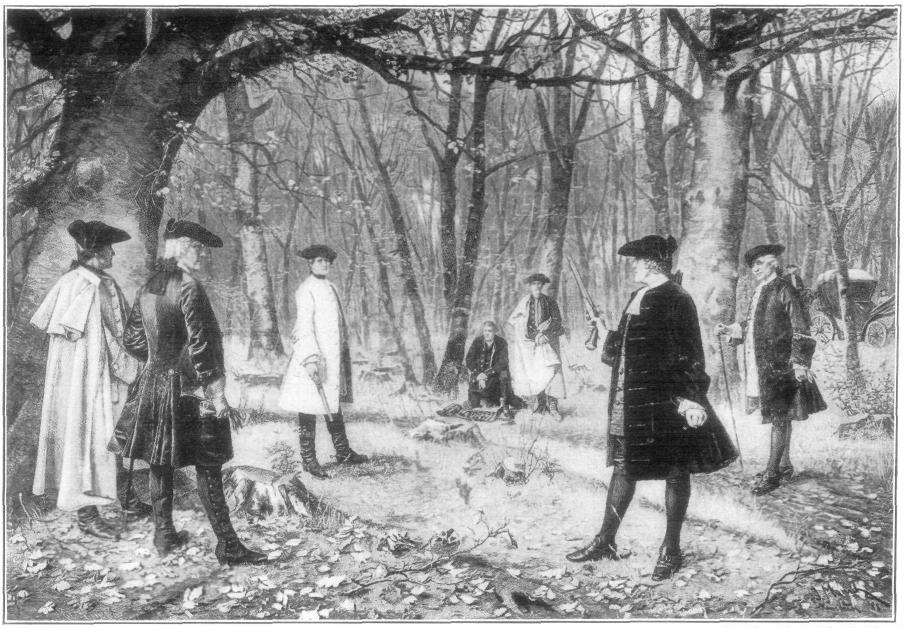

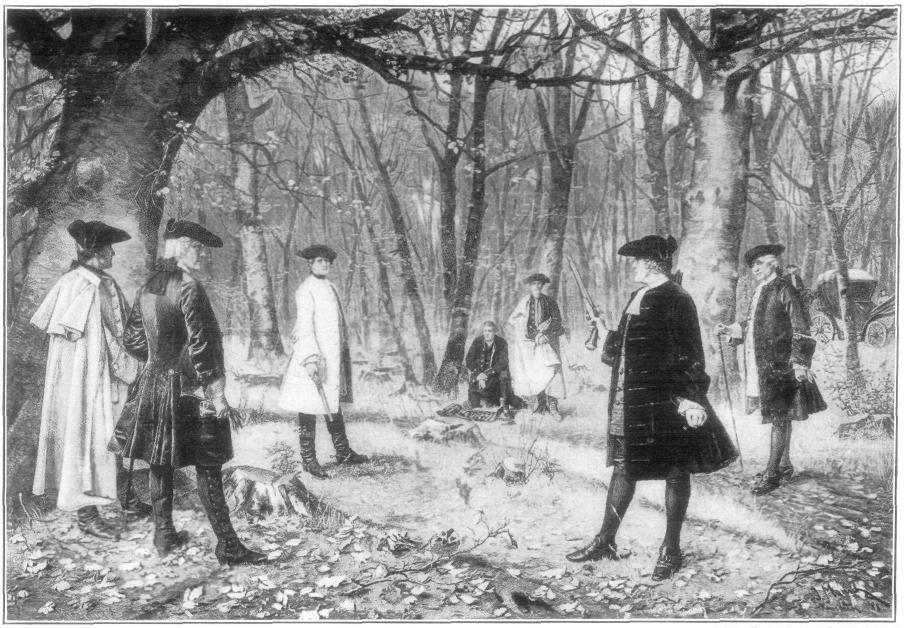

The antagonists met early on the morning of May 16, 1777, at a field a few miles outside Savannah. The principals and their seconds “saluted each other” with exceeding politeness, then examined the pistols to ensure they contained “only single balls.” They agreed to fire at 12 paces and lined up. On a signal from one of the seconds, both parties fired: an instant later, Gwinnett lay writhing with a shattered leg, his own bullet having left McIntosh with only a flesh wound. A few days later, Gwinnett died in agony from gangrene, leaving his widow and three children virtually penniless.

Gwinnett’s death was only the latest in a century of private violence over public causes. The political duel had originated in Europe, where it became common in the 17th century. No less an authority than the great English lexicographer and moral philosopher Samuel Johnson thought the tradition deplorable but necessary. If a man saw his reputation being murdered, Johnson said, surely he had a right to