Year Created: 1775

Collection this Document is Affiliated with:

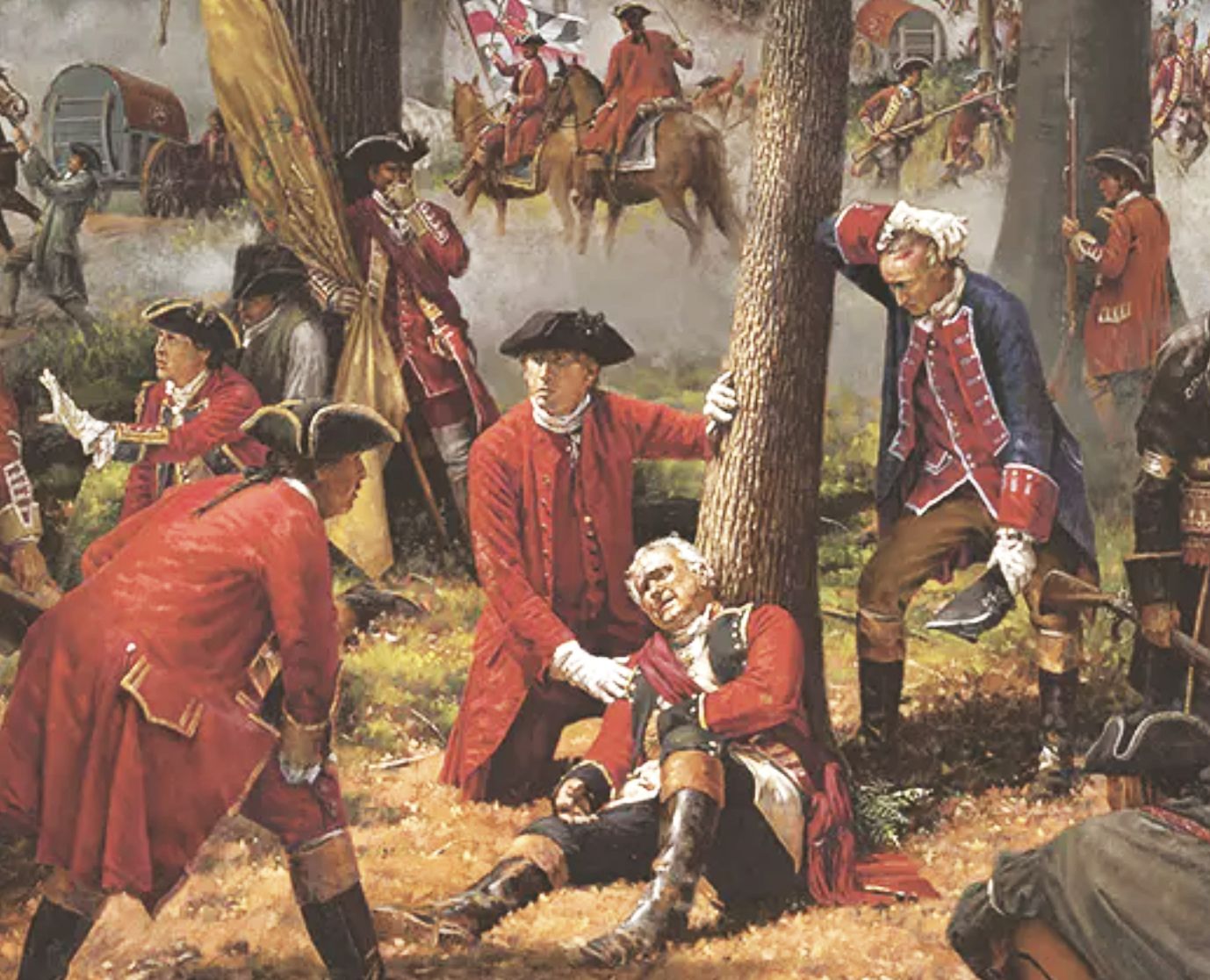

Description: The Braddock expedition, also called Braddock’s campaign or, more commonly, Braddock’s Defeat, was a failed British military expedition which attempted to capture the French Fort Duquesne (modern-day downtown Pittsburgh) in the summer of 1755 during the French and Indian War. It was defeated at the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9, and the survivors retreated. The expedition takes its name from General Edward Braddock, who led the British forces and died in the effort. Braddock’s defeat was a major setback for the British in the early stages of the war with France and has been described as one of the most disastrous defeats for the British in the 18th century.

Categories of Documents:

Monsieur de Contrecoeur, captain of infantry commanding at Fort Duquesne, having been informed that the English would march out from Virginia to come to attack him, was warned a little time afterward that they were on the road. He put spies through the country who would inform him faithfully of their route. The 7th of this month (July) he was warned that the army, composed of 3,000 men of the regular English forces were only six leagues from his fort. The commander employed the next day in making his arrangements, and on the 9th of the month he sent Monsieur de Beaujeu against the enemy and gave him for second in command Monsieurs Dumas and de Lignery, all three of them being captains, with four lieutenants, six ensigns, 20 cadets, 100 soldiers, 100 Canadians, and 600 savages, with orders to hide themselves in a favorable place that had previously been reconnoitred. The detachment found itself in the presence of the enemy at three leagues from the fort before being able to gain its appointed post. Monsieur de Beaujeu seeing that his ambuscade had failed, began a direct attack. He did this with so much energy that the enemy, who awaited us in the best order in the world, seemed astounded at the assault. Their artillery, however, promptly commenced to fire and our forces were confused in their turn. The savages also, frightened by the noise of the cannon rather than their execution, commenced to lose ground. Monsieur de Beaujeu was killed, and Monsieur Dumas rallied our forces. He ordered his officers to lead the savages and spread out on both wings, so as to take the enemy in flank. At the same time he, Monsieur de Lignery, and the other officers who were at the head of the French attacked in front. This order was executed so promptly that the enemy, who were already raising cries of victory, were no longer able even to defend themselves. The combat wavered from one side to the other and success was long doubtful, but at length the enemy fled.

They struggled unavailingly to keep some order in their retreat. The cries of the savages with which the woods echoed, carried fear into the hearts of the foe. The rout was complete. The field of battle remained in our possession, with six large cannons and a dozen smaller ones, four bombs, eleven mortars, all their munitions of war and almost all their baggage. Some deserters who have since come to us tell us that we fought against two thousand men, the rest of the army being four leagues farther back. These same deserters tell us that our enemies have retired to Virginia. The spies that we have sent out report that the thousand men who had no part in the battle, also took fright and abandoned their arms and provisions along the road. On this news we sent out a detachment which destroyed or burned all that remained by the roadside. The enemies have lost more than a thousand men on the field of battle; they have lost a great part of their artillery and provisions, also their general, named Monsieur Braddock, and almost all their officers. We had three officers killed and two wounded, two cadets wounded. This remarkable success, which scarcely seemed possible in view of the inequality of the forces, is the fruit of the experience of Monsieur Dumas and of the activity and valor of the officers that he had under his orders.