Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 4

Editor’s Note: Ronald K.L. Collins is a retired law professor, noted legal scholar, and the author or co-author of 13 books. He recently published Tragedy on Trial: The Story of the Infamous Emmett Till Murder Trial based on the discovery of long-lost transcripts of the trial proceedings. His book was called “groundbreaking” by Janai Nelson, CEO of the NAACP Legal Defence Fund, and Congressman Bobby Rush hailed it as “a long-overdue and indispensable account of the 1955 trial."

September 3, 1955 marked a turning point in the history of racial justice in America. On that Saturday, a crowd gathered at the Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago to attend the funeral for Emmett Till, the young Black boy who had recently been savagely murdered in Mississippi.

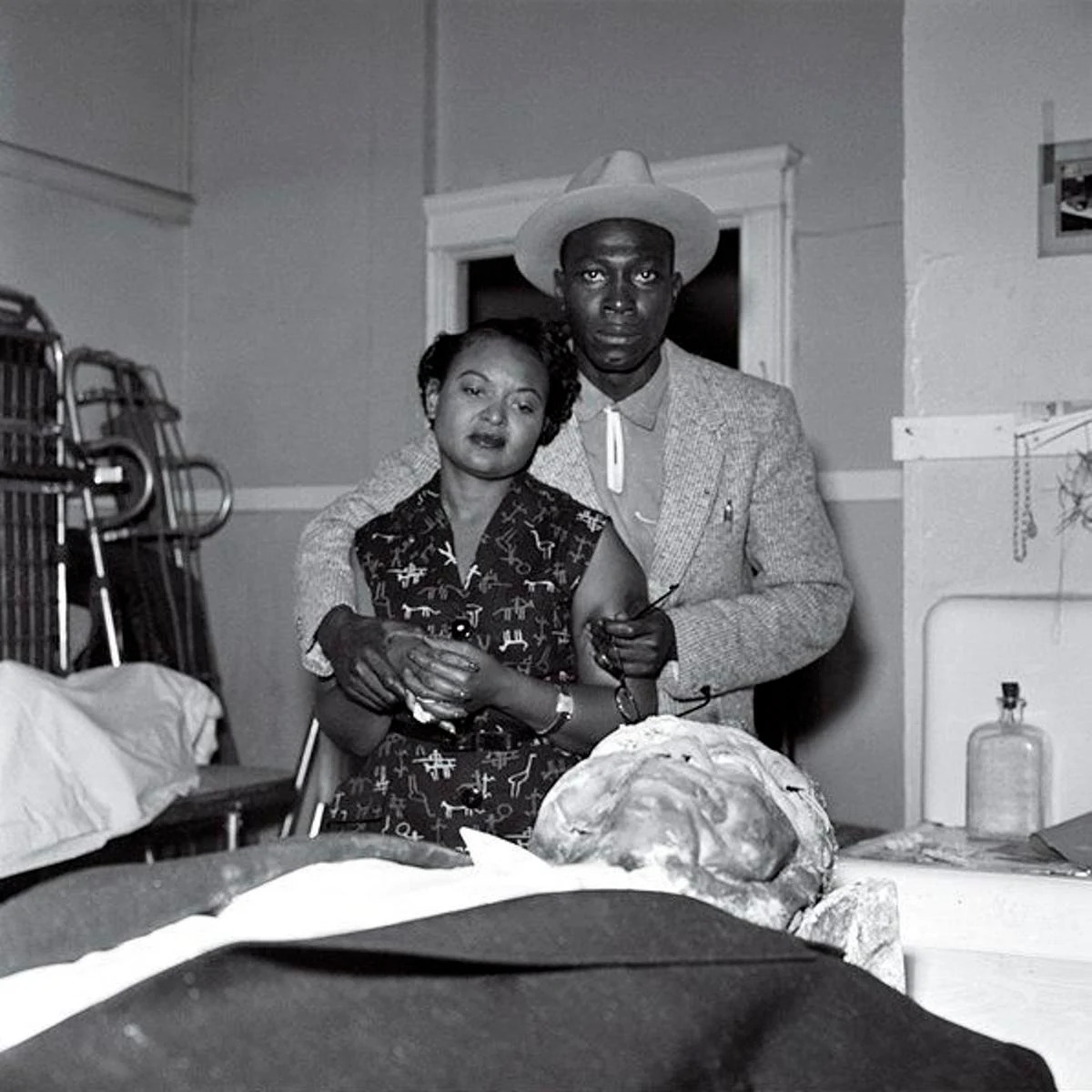

Till’s mother, 33-year-old Mamie Till Bradley (later Mobley), decided to have an open-casket funeral:.“Let the people see what they did to my boy,” she famously declared to the world. For several days, thousands (including the elderly and young alike) came to bear witness to this horrific display of brutality born of bigotry. As Reverend Jesse Jackson put it so well nearly a half-century later, “Mamie turned a crucifixion into a resurrection.”

Two weeks later, Jet Magazine ran a story of the lynching (“Nation Horrified by Murder”) replete with photos taken by David Jackson of the boy’s ghastly disfigured face. Those photos, which only appeared in African American publications, stirred people to act.

Collective suffering was the response, a way to let the light of grace break through the darkness. In so many meaningful ways, the funeral and the photos marked the beginning of the modern civil rights movement.

A Murder Most Foul

It had all begun less than a month earlier. On August 20, 1955, Emmett was 14 years old when he left his Chicago home on a Saturday to board a train to Mississippi for two weeks of fun with relatives. A town near Money was his destination; he would stay at the home of his great uncle, Mose Wright. Jovial and big-city care-free, the boy was unfamiliar with the lethally prejudiced ways of the Deep