Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 7

Authors: Gay Talese

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 7

Editor's Note: Over his sixty-year career, the legendary Gay Talese helped define contemporary literary journalism and is considered one of the pioneers of New Journalism, along with Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, and Hunter S. Thompson. Portions of this essay appeared in his new book, Bartleby and Me: Reflections of an Old Scrivener, just published.

Rising within the city of New York are about one million buildings. These include skyscrapers, apartment buildings, brownstones, bungalows, department stores, shopping malls, bodegas, auto-repair shops, schools, churches, hospitals, day-care centers, and homeless shelters.

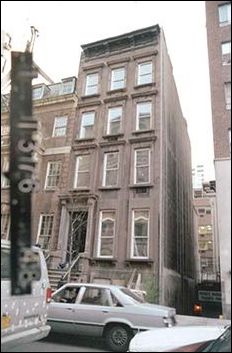

Also spread through the city’s approximately 302 square miles are more than 19,000 vacant lots, one of which suddenly became vacant 17 years ago — at 34 East 62nd Street, between Madison and Park Avenues — when the unhappy owner of a brownstone at that address blew it up (with himself in it) rather than sell his cherished nineteenth-century, high-stoop, Neo-Grecian residence in order to pay the court-ordered sum of $4 million to the woman who had divorced him three years earlier.

This man was an ER physician-turned private practitioner of 66 named Nicholas Bartha. He was a hefty, bespectacled, gray-haired six-footer of formal demeanor and a slight foreign accent. He had been born in Romania in 1940 to resourceful parents — his father Catholic, his mother half Jewish — whose home and gold-mining enterprise were confiscated first by the Nazis and later by the Soviets, prompting Dr. Bartha to vow, many decades later, after a New York judge had favored his ex-wife in the divorce case, and a deputy sheriff had ordered him to vacate 34 East 62nd Street: “I am not going to let anybody evict me as the Communists did in Romania, in 1947 … The courts in New York City are the fifth column.”

In July of 2006, shortly before he set off the explosion from which he would not recover, he addressed his former wife, Cordula, in a suicide note found in his computer: “You always wanted me to sell the house and I always told you. ‘I will leave this house only if I am dead.’”

“He just snapped,” said his lawyer, Ira Garr, referring to Dr. Bartha’s response to the sheriff’s eviction notice. “It was overwhelming for him because, well, he had come to this country with nothing. For many years, his parents and he had scraped together the money to buy the townhouse. This was his American dream, a personification of ‘I’m an American. I’ve made it in America. I own a piece of valuable property in a valuable neighborhood. And I want to live in this place.’ This home was his mistress.”

He had been living

In fact, two of Roosevelt’s sons, Theodore Jr. and Kermit, would become frequent visitors, between the 1920s and 1940s, of the brownstone that Dr. Bartha would own in the 1980s. Beginning in 1927, on the building’s parlor floor, there was a secret club of about two dozen prominent men that included, along with TR’s sons, the banker Winthrop W. Aldrich, the philanthropist William Rhinelander Stewart, the mining expert Oliver Dwight Filley, the naturalist C. Suydam Cutting, and Chief Justice of the New York County Supreme Court, Frederic Kernochan, as well as others who had an interest in international affairs and, in many cases, a working experience in Allied intelligence during World War I. The leader of the group was the real-estate magnate Vincent Astor, who was very interested in espionage and, while on ocean cruises in his private yacht, had often provided the United States government with data he had collected.

Drawing upon the archival papers of Vincent Astor, Kermit Roosevelt, and a few of their friends, the history professor and author Jeffery M. Dorwart described Astor’s group as an “espionage ring” made up of well-born volunteers who were detached from government funding and directives and met on a monthly basis for dinner and conversation “in a nondescript apartment at 34 East 62nd Street in New York City, complete with an unlisted telephone and mail drop.”

The members referred to the site simply as “The Room,” Professor Dorwart explained, and, when they returned from their various world travels, they reported their observations to the members of “The Room,” which resembled an intelligence office, “albeit in an informal and somewhat romanticized manner.”

Professor Dorwart wrote that, although Franklin D. Roosevelt was not on The Room’s roster, “he knew every member well through Groton, Harvard, and New York society business and

Stanfield Turner, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency during the Carter years, said that FDR had dispatched Vincent Astor and Kermit Roosevelt into the Pacific on Astor’s yacht in 1938 in the hope of discovering data about Japanese installations. “It appears that Astor had a thrilling adventure,” Turner wrote, “but did not return with any ground-breaking intelligence ... Astor, though, was a director of the Western Union Telegraph Company, which allowed him to provide FDR with the text of sensitive telegrams and cables. And he had a number of bankers in his Room who allowed him to gather intelligence on the transfer of funds. Roosevelt’s directions to Astor are not on record, but Astor’s messages to Roosevelt suggest that FDR fully approved of these questionable activities.”

Dr. Bartha knew that his brownstone had once sheltered The Room, according to his close friend and colleague Dr. Paul J. Mantia. He said that Bartha had learned about it after a writer doing research had arrived one day to explain the story and then asked to see the parlor floor, claiming that it had historical significance.

Although the building’s rental apartments from earlier times had been converted by Bartha into a single-family residence when he moved in, he nevertheless welcomed and guided his visitor through the spacious entranceway, with its high ceiling, rotunda, antique mirrors, and marble fireplace. He soon warmed to the idea, encouraged by his guest, that they were following in the footsteps of Astor’s social-register spies. Later, Bartha hinted to Dr. Mantia that the space might someday serve as a museum.

The two doctors met in 1991 while working nights in the emergency room of Bronx Lebanon Hospital. At 51, Bartha was fifteen years older than Paul Mantia, a slender, blue-eyed, Brooklyn-born physician with glasses and an amiable and deferential manner that contrasted with Bartha’s strong personality; but the latter’s uncompromisingly high medical standards and ready guidance turned Mantia into his lifelong admirer, emulator, and filial presumptive.

Whenever Bartha would telephone Mantia at home and his wife answered, she would call out to her husband: “Your father’s on the phone!”; and Paul Mantia, who, at thirteen, had lost his father to a

“Bartha was a great doctor,” he said, explaining that physicians in emergency rooms are forced to deal with patients they do not know, patients who sometimes can barely speak because of their injuries or other illnesses; and yet somehow, through a combination of perspicacity and perseverance, Bartha could swiftly and accurately diagnose the situation and then prepare a written report upon which other doctors, perhaps those waiting in intensive-care units, knew from experience that they could rely.

“Whenever Dr. Bartha finished with a patient, everything was clear, everything was done, nothing was incomplete,” Mantia said. “He was scrupulously thorough.”

In 2001, after being friends and medical associates for ten years, Nicholas Bartha and Paul Mantia opened a private practice on the sidewalk level at 34 East 62nd Street. From then on, in the last five years of Bartha’s life, during brief but frequent conversations between patients’ daytime appointments, and during equally brief late-night dinners in hospital cafeterias, Paul Mantia came to know more and more, little by little, about this serious, privately sad, but never sentimental man who was his mentor.

* * *

Nicholas Bartha was born in Romania to parents of Hungarian ancestry. Although his family identified itself as Catholic, his maternal grandfather was a rabbi. As a child during World War II, he hid with others in caves belonging to gold-mining families, some of them Jewish, all hoping to elude the Iron Guard’s anti-Semitic, ultra-nationalist political henchmen when Romania was allied with Nazi Germany.

Later, when the Nazis retreated, the Russians quickly moved into Romania to create more misery. Nicholas could recall seeing horse-drawn carriages bearing the dead bodies of those who had challenged the communists in 1946. In the early 1950s, his father spent two years in prison on charges, never proven, that he was hoarding gold somewhere in the Carpathian Mountains not far from where he had operated his mine, before it was nationalized.

Although Nicholas managed to finish high school, he was banned from attending college as a medical student because of his father’s political problems. In October of 1956, while listening to Radio Free Europe and Voice of America, he was heartened to hear of the Hungarian Revolution in Budapest, but weeks later, the uprising was crushed, 200,000 Hungarians became refugees, and the Soviets regained their dominance.

During these years, Nicholas was working in factories and operating lathe machines—cutting, sanding, grooving, and drilling with such proficiency that, by 1960, he had gained enough favor to be allowed to enter medical school in the northwestern Romanian city of Cluj. But, in 1963, after both parents

In fact, hours before destroying his brownstone in 2006, in the suicide note he emailed to a number of people — including his attorney, Ira Garr; his computer teacher, Alejandro Justo; his best friend, Paul Mantic and his worst friend and ex-wife, Cordula — there were references to his feelings shaped by World War II and the Cold War years in his native Romania"

He had fled Romania in March of 1964. He was then twenty-four. A friendly source within the Romanian security service had told him that his arrest was imminent, explaining that, because his imprisoned parents were not satisfying their jailors, he would soon be held hostage. On March 15, Nicholas Bartha arrived in Israel. He remained there for nine months, living and working on a kibbutz and studying Hebrew. He then moved to Italy after learning that his parents, recently released from jail, had relocated in Rome, assisted by a relative who was a priest at the Vatican.

After six months in Rome, Nicholas and his parents applied for a parolee visa to enter the United States, which was granted in late June of 1965. They settled in an apartment in Rego Park, Queens, where Nicholas found work on the assembly line of the Bulova Watch Company, producing gadgets for timing devices and receiving the minimum wage of $1.98 an hour. His mother, Ethel, got a job in a beauty salon and his father, Janos, became a cook at the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan.

A year later, Nicholas quit Bulova, where his advancement was stalled because he wasn’t a citizen, so he found work in Queens at the Astra Tool and Instrument Manufacturing Company, soon earning $5.00 an hour and saving every penny. In his journal, he noted that he always walked to work, never bought a car, and, though tempted, never paused on his way to work to have breakfast at the International House of Pancakes on Northern Boulevard.

In 1967, he obtained a green card and was accepted as a medical student at the University of Rome. During the next seven years, while attending medical school, Nicholas would return each summer to live with his parents in Rego Park and resume working as a lathe machinist at Astra Tool, receiving several raises along

By this time, he had become a U.S. citizen, and, in the spring of 1974, he graduated from medical school. He had also been having a year-long affair with a young woman he had met as a fellow student at the University of Rome. Her name was Cordula Hahn.

She was a petite, soft-spoken, plain but cheerful thirty-year-old brunette who had earned a PhD in German literature and later worked as an editorial assistant at an Italian publishing firm. She had lived in Italy for fourteen years, arriving there as a teenager in 1960 from the Netherlands with her parents.

They had been wartime Czechoslovakian refugees who had left their Nazi-occupied homeland in 1938 for the Netherlands, settling in the village of Bilthoven, an affluent community about twenty miles east of Amsterdam. Cordula was born there in 1942. Her father was Catholic, her mother Jewish, and, even though she converted to Catholicism, she was forced to publicly identify with her Jewish background by wearing a star on her clothing when the Germans ruled over the Netherlands.

In Italy, Cordula’s academic and well-to-do parents found contentment and social acceptance — although, in 1973, they were not happy with Cordula’s choice of a boyfriend. For reasons never made clear to Nicholas, her parents disapproved of him, and, not one to forget a slight, he held a grudge against them thereafter.

In 2002, while testifying in the divorce trial, he mentioned the lack of warmth between himself and his mother-in-law. In his 2006 suicide note, he described with a condemning eye the paternal side of Cordula’s family. He wrote that her father was a left-wing Bohemian German born of a fascist family.

But, in spite of her parents’ misgivings about Nicholas, she followed him from Rome to the United States in 1974 after he had completed medical school. For the next three years, though still not married, she lived with him in the rent-free basement apartment of the multi-family home in Rego Park, Queens that Nicholas and his parents, pooling their resources, had purchased seven years earlier, in 1967.

In 1974, at Elmhurst General Hospital in Queens, Nicholas began serving a two-year internship, followed by a one-year residency. Cordula, who spoke five languages, was employed in Manhattan within the cultural section of the consulate-general of the Netherlands, which had also arranged for her visa.

In 1977, she became pregnant. Nicholas would have preferred an abortion, but she insisted on having the child — a daughter, Serena, born seven months after the couple was married in a civil ceremony in Queens. They then moved from their basement dwelling into an upper-floor apartment in the Bartha building, contributing $200 a month toward the family fund for household maintenance, which matched the monthly rent of the tenants they had replaced.

In December of 1978, Cordula had

“She developed post-partum depression and later became psychotic after she had two daughters. She refused treatment. In 1980, I was going to divorce her, but changed my mind because of the children.”

In 1980, Nicholas and his parents, again pooling their resources, bought the Manhattan brownstone at 34 East 62nd Street for $395.000. It was Nicholas who had encouraged their move to Manhattan.

His friend Dr. Paul Mantia remembered hearing Nicholas describe the thrill of standing in front of the fountain at Grand Army Plaza on 59th Street one afternoon, with the Plaza Hotel behind him and the entrance to Central Park not far away, and thinking: This is where I want to live someday.

Even before the family had moved into the brownstone, it was decided that Nicholas, his wife, and their two daughters would live on the upper two floors, his parents on the floor below. The parlor floor would be used only as a spacious entranceway, a prideful piano nobile or main floor. On the sidewalk level of the brownstone, where, in later years, Nicholas and Paul Mantia would have their private practice, Nicholas’s mother, Ethel, planned a beauty salon.

Indeed, it was a business that would succeed almost immediately — serving such clients as the wife of Anthony Quinn, and Barbara Walters, who had her legs waxed there. But in or around 1990, a little more than a year after Ethel’s salon had opened, it was shut down following complaints in the neighborhood that the street was not zoned for such a commercial enterprise.

In fact, Dr. Bartha did not want a divorce, but his wife did, and he felt obliged to hire an attorney. He selected one of the leading matrimonial lawyers in New York City, Ira Garr. When the Manhattan federal court judge Kimba Wood needed legal representation in ending her fourteen-year marriage to the political columnist Michael Kramer, she summoned Ira Garr. He also stood by Ivana Trump in her divorce from Donald Trump, and he handled the divorce case of publisher Rupert Murdoch involving his third wife, Wendi Deng.

Garr was introduced to Dr. Bartha by a fellow attorney and friend of Dr. Paul Mantia, the latter experiencing much concern about his mentor’s morale and need of legal guidance in the aftermath of the sudden departure of Cordula and the daughters from the brownstone. On October 17, 2001, after she and her daughters had moved briefly to Brooklyn before renting an apartment in Washington Heights, she left a note on a chest of

During the final year of his life, Dr. Bartha would chat briefly with his next-door neighbor, Brian Sugrue, whenever they met on the brownstone’s steps.

The already-stout Dr. Bartha had gotten even heavier of late, perhaps exceeding 300 pounds. He was not only moving slowly and haltingly while gripping the rail for support, but he also climbed down the steps backward.

One dark and chilly afternoon in February 2006, Dr. Bartha paused for a moment as he reached the sidewalk, and, turning to Sugrue, he said in an offhand manner, “You know, February is the most popular months for suicides.” He paused again, then asked: “Do you know why? Lack of vitamin D. Lack of sunshine.”

Without waiting for Sugrue’s response, Bartha turned away and trudged toward his parked car. Sugrue gave no further thought to this strange exchange until five months later.

It is quite possible that Bartha had contemplated killing himself in February or at some other time. Dr. Paul Mantia remembered entering his office in the Bartha brownstone one morning and noticing that all of his own framed medical certificates that had been hanging on the wall had been removed. After walking into Bartha’s office next door to report this, his friend at first said nothing. Then, reaching slowly into his jacket pocket for his car key, he handed it to Mantia.

“They’re in the back seat of my car,” Bartha said.

“What’s my stuff doing in the back of your car?”

“Don’t ask,” said Bartha.

Bartha remained straight-faced and silent, so Mantia accepted the key and headed out to scout some of Bartha’s favorite parking spaces in the neighborhood. Within a block or so, finding the Toyota Echo, he retrieved the certificates and returned to the office to rehang them on the nails that were still in place. He then donned his white lab coat and sat behind his desk, waiting for the receptionist to bring in his first patient.

Even in his solitude, the irritations of the outside world reached Bartha. With limited success, he closed his front windows in an effort to avoid the smoke filtering in from the grill operated by the food vendors of a super-sized pushcart on 62nd Street and Madison Avenue. He also stayed away from his terrace because it overlooked the coal-burning pizza ovens in the outdoor dining area in the back of the Serafina restaurant, on East 61st Street. On his computer, he wrote:

Directly across the street, Dr. Bertha observed with displeasure the headquarters of the multi-millionaire businessman and investor Ronald Perelman. On the same block where Bertha’s mother had been forced to close her beauty salon due to presumed zoning violations, Mr. Perelman oversaw his commercial empire.

“The Fleming School was bought by Mr. Ronald Perelman and is now office space for Revlon," Bartha complained. “At 37 East 62nd, another office building. . . This is a residential and public-use zoned street. It is not for connected people.”

During the late afternoon of Friday July 7, 2006, while Bartha was on duty at Mount Vernon Hospital in Westchester County, a messenger visited the brownstone office and gave an envelope to the receptionist. It had come from the New York City Sheriff’s Office. It contained a final warning instructing the doctor to vacate his residence. She placed it on his desk, and later in the afternoon, left the office for the weekend.

At this time, Dr. Mantis was vacationing in Canada with his wife and nine-year-old son. He was due back at the office at nine o’clock on the following Monday morning, July 10. But, less than an hour before he was scheduled to arrive, Dr. Bartha was preoccupied with filling the place with infusions of gas diverted from a pipe in the basement.

Bertha was alone in the building when it eventually blew up. To prevent anyone from entering, he had positioned himself at the front window of the reception room of his street-level office. Having already read the sheriff’s eviction notice that he had to vacate, he had contacted his secretary and told her to cancel all of that day’s appointments. There was no doubt that he planned to die early that morning in the brownstone that he valued more than his life.

Before dawn, he had already emailed his suicide note to various people. It was doubtful that anyone had yet read it as he stood waiting behind his office window facing the street, having no idea how long it would take for the gas to circulate through his body and achieve its desired result.

Shortly before 6:30, the flow of gas was strong enough to have penetrated the basement and main floor of the building next door, the Links Club, a five-story classical brick structure at 36 East 62nd Street. The first person to smell gas there was a forty-year-old waiter and native of Ecuador named Jack Vergara, who was on duty to help with the breakfast that would be served to the members.

Walking to work earlier, Jack Vergara might well have been among the last of those whom the doctor would see.

After entering the vestibule of the Links Club shortly before 6:30 and exchanging greetings with the night watchman, Vergara said: “I smell gas.” The watchman shook his head, indicating that he smelled nothing.

He suspected

The cook objected: “The chef will be angry when he shows up and sees we don’t have the bacon ready,” adding that the members would probably also be unhappy with the restricted menu. “Cold breakfast today,” Vergara repeated. He was only a waiter, but in the absence of his boss, the general manager, he was asserting his status as a senior employee. He had been working at the Links Club for nearly twenty years. And so, on this morning, a cold breakfast was served, and, having explained the circumstances to each arriving member, there were no complaints.

It was during the latter part of the breakfast service, somewhere close to 8:30, that Vergara first heard what he later described as a “big tremor,” a loud noise accompanied by a quivering sensation in his body that he initially attributed to the collision of a dump truck outside, or maybe a major malfunctioning of its engine.

However, as he peered down from the fourth-floor window, overlooking the street in front of the club, he saw nothing amiss. Then, after going down to the third floor and looking through one of the side windows, he saw huge clouds of dark dust rising into the atmosphere and then realized, much to his amazement, that the familiar sight of the old brownstone next door, a fixture since 1881, was no longer there.

Crumbled by the explosion, it was now vaporized within a mirage of cascading chaos, a fiery heap of fallen floors that steadily covered the sidewalk and curb with an ascending mound of the charred and splintered remnants of Dr. Bertha’s household fixtures and personal possessions — his burned books, his crushed computers, tiny pieces of his shoes, clothing, spectacles, his bed, microwave, eating utensils, bathroom tiles, carpeting, banisters, door knobs, chunks of the half-intact stone stoop, the battered newel posts, the contorted and loosely hinged French-style iron front door.

Christopher Gray of the Times wrote that it “staggers like a drunk at the top of the stairway.” There were also, spread throughout the remains, pieces of a few of Dr. Bartha’s late mother’s hair dryers that

Completely unaware of the calamity — which would in time injure ten firefighters and five passersby, and damage the interiors of thirteen apartments in the 84-unit Cumberland House — was a 66-year-old financier and Links member named Eric Gleacher. who, as Bartha’s house was tumbling down, was fully concentrated on soaping himself under a shower in one of the club’s guest rooms on the fourth floor.

“While I was shaving, I heard a loud noise,” Mr. Gleacher said. “It sounded like a backfire in a furnace system. I was not concerned, as the noise was not particularly loud and I had been trained in explosive ordnance while on active duty with the Second Marine Division at Camp Lejeune in the 1960s. I know what a blast from C-4 plastic sounds like, as well as dynamite and hand grenades. This noise wasn’t close to the percussion from those explosives.”

“I could see debris in the street and a woman lying on the sidewalk almost at the northeast corner of Madison and 62nd. My first reaction was that someone had tried to blow up Perelman’s office,” he said, referring to the frequently litigious and four-times-divorced mogul. “Ronald was a client and a friend with whom I had worked many times. I helped him acquire Revlon in the 1980s and I knew him well. He was thoroughly honest and very tough in his business dealings and, as a result, had made enemies who would like nothing more than to see him taken down a peg or two.”

“I dressed quickly and opened the door to my room. Much to my surprise, right outside stood a New York firefighter, ax in hand. He told me I’d better hustle down the stairs and vacate the premises. There was broken glass in the front-door area and the attendant on duty was cut and bleeding. I picked my way around the debris and crossed to the north side of 62nd Street. I immediately saw the flames, which looked ferocious and climbed all the way up the west firewall of the Links, licking the roof after reaching the top. I immediately assumed that the Links building was surely going to be consumed by the flames. Within seconds of that, though, the NYFD demonstrated what it could do. They turned on the hoses and washed the side of the building with water, and the flames fell away with remarkable speed.”

Ronald Perelman was not in his office at the time of the incident, but his secretary, seated at

Another employee in Perelman’s office thought at first that she was in the middle of an earthquake. She took a photo of the destruction across the street, and it ended up on the front page of the next day’s edition of the New York Daily News, with a photo credit.

Throughout the afternoon, television-news helicopters hovered over the neighborhood, and, although the White House announced that the blast did not appear to be the work of terrorists, Dr. Bartha’s notoriety quickly spread around the world via television and the print media. Some headline writers began referring to him as “Dr. Boom.” At Camp Fallujah, west of Baghdad, a Marine Corps lieutenant named Renny McPherson saw images of the burning brownstone on the television set in his mess hall, and he immediately emailed his parents, who lived on 62nd and Park Avenue—his father was also a member of the Links—and asked: “Are you all right?”

When Dr. Paul Mantia arrived at the building surrounded by the police vehicles and fire trucks, he was relieved to learn that the secretary had not been inside. Although his office was buried under piles of rubble, he had fortunately made duplicate copies of his medical certificates and kept them at home. Also at home, on his computer, was a message that Dr. Bertha had emailed him an hour or two before the explosion.

“Paul, I am sorry, but I cannot put up with this situation any more. I am glad you passed your board recertification. It made my decision easier. I hope your vacation was good. “

Dr. Bartha had also emailed two final messages to his ex-wife. In one he wrote:

The other message to her read:

After the firemen had recovered Dr. Bartha’s unconscious body from the rubble, it was rushed to the emergency room of the New York Presbyterian Hospital. Almost half of his body was charred with second- or third-degree burns, and, during his time in the hospital, he was unable to speak or communicate in any way. He died there on July 15, five days after he had arrived. The next week, he was buried in Queens.

“It was a small ceremony for family only,” said the funeral director, meaning that none of Dr. Bartha’s close friends, such as doctors Mantia and Nazario, were invited. Cordula did appear at

A gravedigger at the Cypress Hills Cemetery told the New York Daily News: “There weren’t any tears. Nobody was really busted-up ... A preacher read a short prayer from the Bible, then we lowered the white coffin.”