Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2019 | Volume 64, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2019 | Volume 64, Issue 1

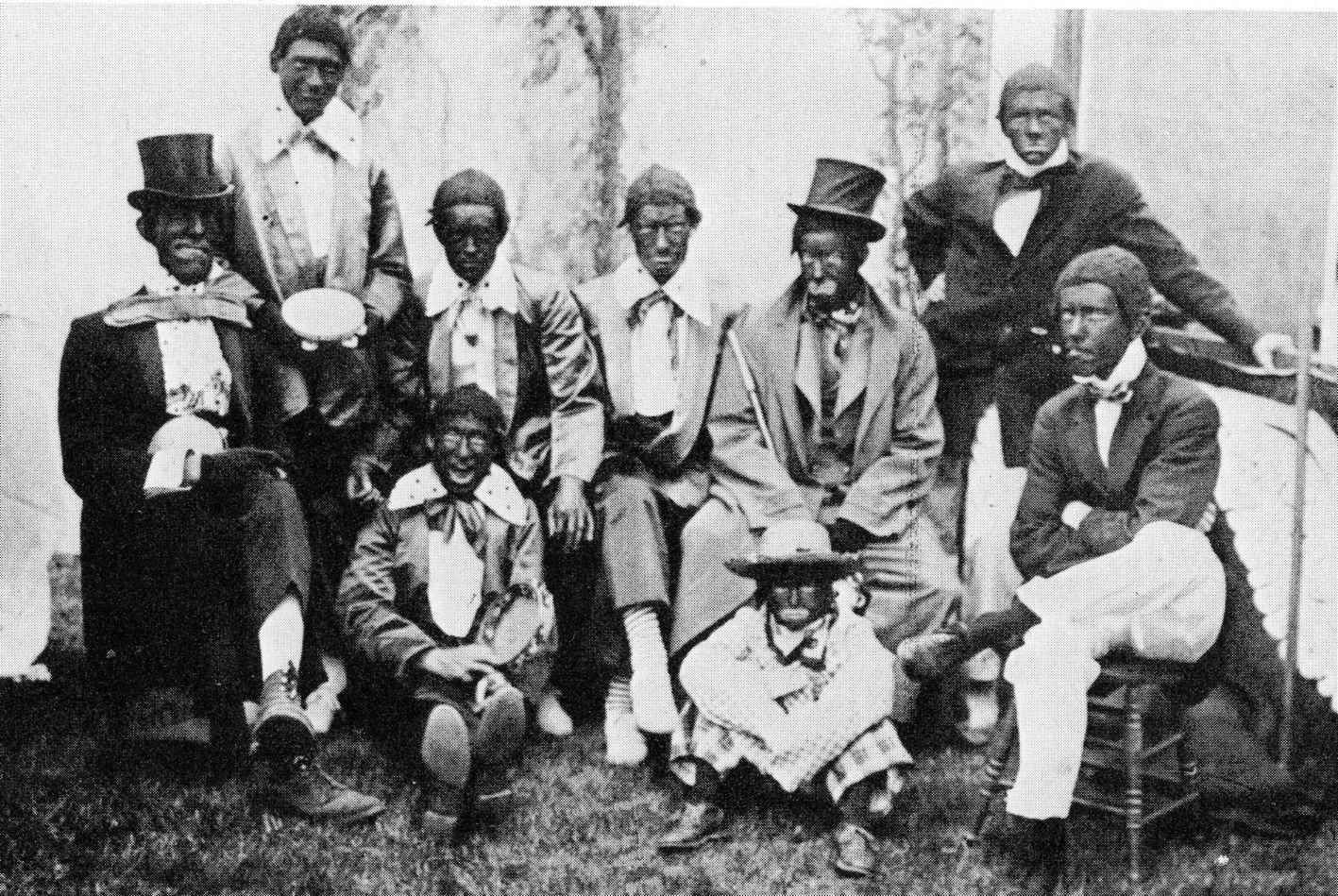

The recent furor over the use of blackface by Virginia's governor and attorney general while they were in college reminds us of a sad chapter in our history – the long tradition of minstrel shows in which whites covered their faces with burnt cork or grease paint in order to profit from denigrating African-Americans.

We reprint below a 1978 article from American Heritage by historian Robert Toll, one of the first scholars to study this uniquely American form of popular culture and its impact.

Minstrel shows began with the creation of the character of "Jim Crow" by white performer Thomas Rice in 1828, and his eccentric song and dance soon became a national sensation. Interestingly, minstrel shows were more popular in the North than Dixie, especially in urban areas. The audiences were "large, boisterous, and hungry for entertainment," says Toll. "They hollered, hissed, cheered, and booed with the intensity and fervor of today’s football fans."

The minstrels had a long-lasting impact, with cruel stereotypes that echoed in popular culture for 150 years. Abolitionist Frederick Douglass decried blackface performers as “the filthy scum of white society, who have stolen from us a complexion denied to them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow citizens.”

The minstrel shows did expose whites to African-American music and dance. For example, multiple traditions blended together in the songs of Stephen Foster such as "Oh! Susanna", "Old Folks at Home" ("Swanee River"), and "My Old Kentucky Home." And there is a long history of whites eagerly learning dances from inventive African-Americans, from before the Civil War to the Charleston, the Hustle, and Hip-Hop.

Toll points out that after 1900 minstrel shows made possible the “first large-scale entrance into American show business” for blacks as they broke the barriers they had faced before. But to make a living these performers often had to act out heartbreaking stereotypes such as the “Two Real Coons” played by Bert Williams and George Walker. On stage and in silent films, Stepin Fetchit played “Lazy Richard” and Willie Best “Sleep n' Eat.”

Many early jazz performers such as Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong owed a debt to minstrel traditions. “All the best (black) talent of that generation came down the same drain,” wryly recalled W.C. Handy, the "Father of the Blues."

The magic feet of Bill "Bojangles" Robinson stole the stage from Shirley Temple. The fabulous Nicholas Brothers, Fayard and Harold, were Fred Astaire's heroes on the dance floor. (Watch them dance while Cab Calloway and his band play “Jumpin' Jive” in what is probably the