Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April/May 1978 | Volume 29, Issue 3

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April/May 1978 | Volume 29, Issue 3

NOTE: this article has been updated and reissued in the Winter 2019 issue. Click for the new version.

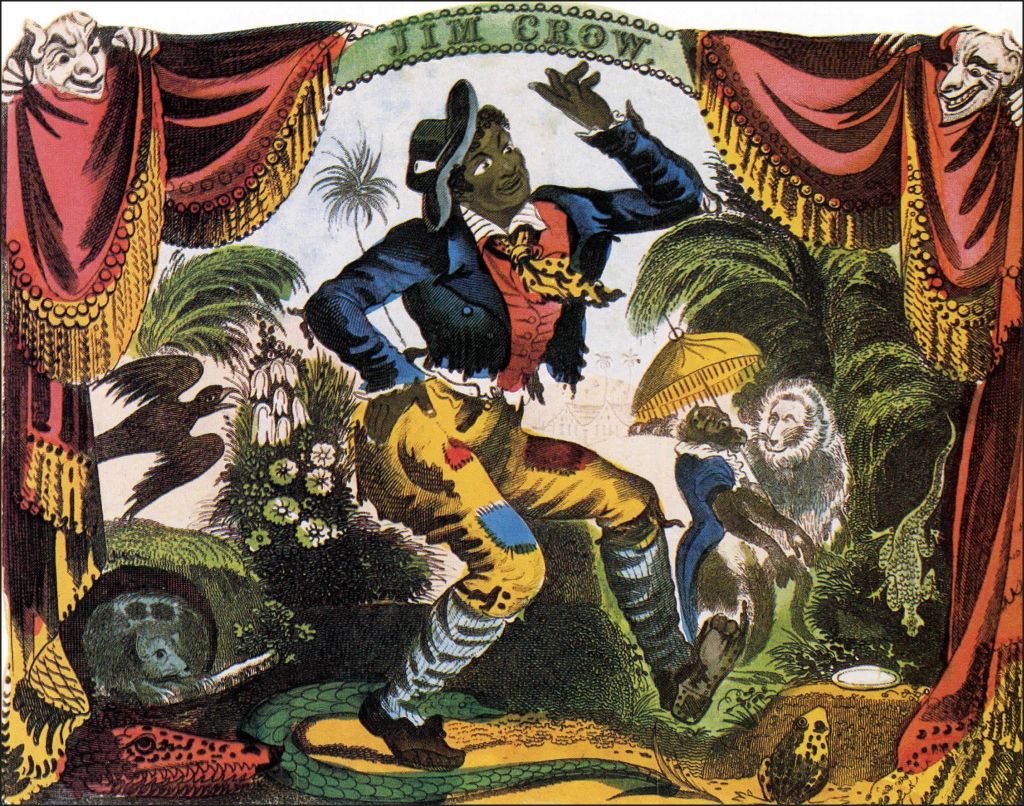

It is on our supermarket shelves, in our advertising, and in our literature. But most of all, it is in our entertainment. From Aunt Jemima to Mammy in Gone With the Wind, from Uncle Remus to Uncle Ben, from Amos ‘n’ Andy to Good Times, the inexplicably grinning black face is a pervasive part of American culture. Only recently have black performers been able to break out of the singing, dancing, and comedy roles that have for so long perpetuated the image of blacks as a happy, musical people who would rather play than work, rather frolic than think. Such images have inevitably affected the ways white America has viewed and treated black America. Their source was the minstrel show.

Before the Civil War, American show business virtually excluded black people. But it never ignored black culture. In fact, the minstrel show—the first uniquely American entertainment form—was born when Northern white men blacked their faces, adopted heavy dialects, and performed what they claimed were black songs, dances, and jokes to entertain white Americans. No one took minstrel shows seriously; they were meant to be light, meaningless entertainment.

But it was no accident that the blackface minstrel show developed in the decades before the Civil War, when slavery was often the central public issue, no accident that it dominated show business until the 1880’s, when white America made crucial decisions about the status of blacks, and no accident that after the minstrel show died, the basic stereotypes it had nurtured endured-the happy, banjo-strumming plantation “darky,” the loving loyal mammy and old uncle, the lazy, good-for-nothing buffoon, the pretentious city slicker.

For better or worse, the American people made the minstrel show what it was.

America’s cities mushroomed after 1820, and American show business grew along with them. The new city audiences were large, boisterous, and hungry for entertainment; they hollered, hissed, cheered, and booed with the intensity and